For those following from afar the various projects geared toward additive construction on the Moon or Mars, one thought may not have occurred: what about oxygen? How will astronauts breathe while building the space habitats of the future? It certainly never occurred to this writer, who didn’t consider the task of lugging oxygen tanks up to the Moon for extended periods of use.

To tackle the issue of regular oxygen supply on the Moon, the European Space Agency (ESA) is exploring the possibility of an oxygen extraction plant that would rely on technology that already exists on Earth. Metalysis says that oxygen is a byproduct of the metal refinement process it uses for manufacturing metal powders for 3D printing. While that oxygen did not previously have an application on our home planet, the company realized it could serve profound purposes for space.

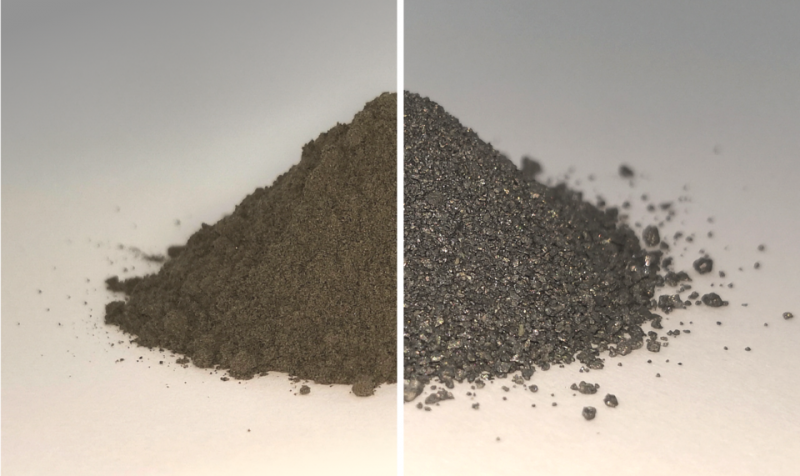

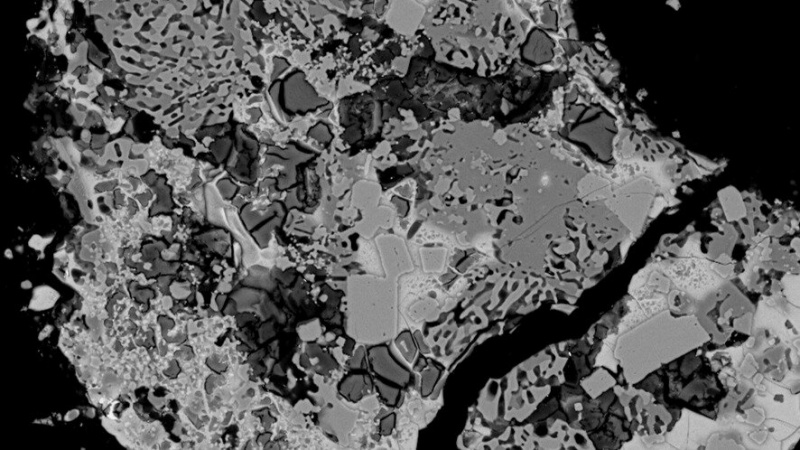

Moon dust, or lunar regolith, is the fine layer of rock that coats the Moon and is not that different from Earthly minerals. It is made up of 45 percent oxygen bound to metals such as iron and titanium. The process to extract the oxygen is known as molten salt electrolysis. The minerals placed in a molten calcium chloride salt heated to 950°C within a specialized chamber before an electric current is applied. The oxygen is drawn to an anode, leaving the metal powders behind.

“Some years ago, we realized that the seemingly unimportant by-product of our terrestrial mineral extraction process could have far-reaching applications in space exploration,” says Ian Mellor, managing director at Metalysis. “We look forward to continuing to explore with ESA, and our industrial partners, how to get our Earthly technology space-ready.”

The ESA was able to demonstrate that this process can be applied to regolith in January 2020 when it set up a prototype oxygen plant at the Materials and Electrical Components Laboratory of the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC), based in Noordwijk in the Netherlands.

“At Metalysis, oxygen produced by the process is an unwanted by-product and is instead released as carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, which means the reactors are not designed to withstand oxygen gas itself,” said Beth Lomax, of the University of Glasgow, who worked on the project. “So, we had to redesign the ESTEC version to be able to have the oxygen available to measure. The lab team was very helpful in getting it installed and operating safely.”

As the project continues, the team is exploring the possibilities of collecting and storing the oxygen, as well as 3D printing with the metals that result from the process. This includes answering questions such as whether or not these metals could be 3D printed directly or require refinement. The exact combination of metals within the regolith differ depending on where on the moon they are acquired.

Advenit Makaya, the ESA materials engineer overseeing the project, said, “The project will help us learn more about Metalysis’ process, and may even be a stepping stone to establishing an automated pilot oxygen plant on the Moon – with the added bonus of metal alloys that could be used by 3D printers to create construction materials.”

The oxygen would ultimately be used both to provide breathable air and rocket fuel, while the metals could be used for 3D printing parts on the Moon, including for the construction of habitats. This would make it possible to sustain life on the Moon without the cost of sending materials from Earth.

“Being able to acquire oxygen from resources found on the Moon would obviously be hugely useful for future lunar settlers, both for breathing and in the local production of rocket fuel.” ESA research fellow Alexandre Meurisse said. “And now we have the facility in operation we can look into fine-tuning it, for instance by reducing the operating temperature, eventually designing a version of this system that could one day fly to the Moon to be operated there.”

Metalysis, meanwhile, is refining the oxygen extraction technique in order to produce as much of the gas as possible to maximize its use in lunar applications. Modifications include changing the electrical current and reagents to increase the amount of oxygen. At the same time, they are attempting to lower the temperature needed to produce it in order to reduce energy costs. The chamber will also be made smaller so that it can be sent to the Moon more efficiently.

Additionally, ESA and Metalysis have initiated a challenge seeking outside engineers to develop an in-process monitoring system for tracking oxygen production. The overarching goal of the project is to create a pilot plant that would be able to operate sustainably on the Moon, with the first technology demonstration set for the mid-2020s.